The Future of Aquaculture, part three

-

English

-

ListenPause

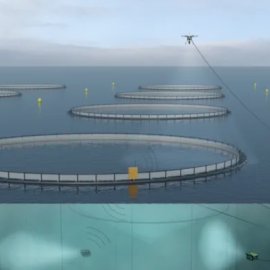

[intro music] Welcome to World Ocean Radio… I’m Peter Neill, director of the World Ocean Observatory. Aquaculture as we have known it to date is based on the idea of pens floating offshore filled with fish susceptible to disease, fed and treated with feed loaded with antibiotics, generating notorious amounts of waste, and vulnerable to breech, thus the escape of possibly sick or mutated fish into the wild. All of these circumstances, true in part, certainly in theory, brought the concept of offshore aquaculture into regulatory and public disrepute. Offshore aquaculture has progressed substantially both in technique, reliability, and scale. Innovations include surface cages, submersible cages, vessel aquaculture, and large fish farms permanently moored in deep waters. According to a 2021 report by the Global Aquaculture Alliance, “a Norwegian company has built the world’s largest offshore fish pen, some 110 meters wide…which can hold 1.5 million fish, and is equipped with 22,000 sensors to monitor various environmental parameters and the behavior of the fish. Another example is that of a Chinese project to build the world’s first 100,000-ton intelligent fish-farming ship…250 meters long and 45 meters wide…able to avoid typhoons, red tides and other severe weather and environmental issues while carrying out aquaculture operations anywhere in the world…and expected to produce 400 tones of high value marine products each year.” These enormous pens and moving vessels can be operated remotely to control feeding, sampling, monitoring, and surveillance. Yes, you heard it right: massive factory aquaculture, at sea, no one aboard. Imagine that ship in the Arctic. The challenge for aquaculture is one primarily of place. Is it better for these activities to exist in the ocean or, ironically, on land? Is it better for them to be closed systems, environmentally isolated, accessible to maintenance, repair, and emergency response? What are the advantages and disadvantages with regard to environmental protection, food security, and social impact? Let’s assume that it is less expensive, less bureaucratically complicated, with lesser labor and tax expense, and with greater profit to locate offshore. But that said, as usual the cost of failure, monumental die-off and population collapse, and consequential damage to other species and the ocean itself is never included in the cost-benefit analysis. It really is no different than an offshore oil platform, enormously productive and profitable and until technical breakdown, accident disrupts the process with catastrophic, amplified destruction and reparation cost far beyond the immediate project, leading to bankruptcy and intervention paid for not fully, if at all, by the company or its insurers, with only government to assume the full and ongoing expense. Consider the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico and you get some idea of what failure can bring. There are various alternatives to consider: on-land aquaculture, with similarly advanced technology but as closed systems that use adjacent salt or fresh water treated before and after its primary use as a production habitat for growth and protection. The spectrum of projects alleviates, in part, the issue of place, although there is always community objection, permit conflict, fear of change, and real estate protection issues to complicate the problem. One project might be designed as an on-shore processing center to receive production from offshore pens. A second might use freshwater from the locale aquifer. A third might re-purposes a waterfront site, be powered by an adjacent power utility, and use salt water from the adjacent ocean, treated and recycled, with immediate land-based access for accident response. The integration of ocean geothermal and solar energy technology might additionally serve the efficiency and economy of them all. We have limited the ocean’s capacity to serve our food security needs. One expert has suggested that if we were to stop fishing altogether, literally tie up the global fleet for five years, the ocean might have time to regenerate its natural capacity. But what will we do in the meantime? And would we then begin again our practice of unlimited harvest and consumption so that in another five years we would be back where we started. Technology is not a tyranny. It can be used against us, but it can also be the transformational invention that drives change. Aquaculture is a singular example of the best of human endeavor to solve a problem, to meet a challenge, and, in this urgent case, one method or another, a means by which to feed our people. We will discuss these issues, and more, in future editions of World Ocean Radio. [outro music]

In this brief series we're exploring disruptive technologies for aquaculture, specific initiatives and other advancements to improve efficiency and safety as a positive contribution to our future food supply and global health. This week we are discussing the challenges to aquaculture, the perils of some new unmanned technologies on the horizon, the pros and cons of offshore systems, and the spectrum of alternative projects that could alleviate the typical pitfalls of offshore aquaculture.

About World Ocean Radio

Peter Neill, Director of the World Ocean Observatory and host of World Ocean Radio, provides coverage of a broad spectrum of ocean issues from science and education to advocacy and exemplary projects. World Ocean Radio, a project of the World Ocean Observatory, is a weekly series of five-minute audio essays available for syndicated use at no cost by college and community radio stations worldwide.

World Ocean Radio is produced in association with WERU-FM in Blue Hill, Maine and is distributed by the Public Radio Exchange and the Pacifica Network.

Available for podcast download wherever you listen to your favorites.

Image

Artistic rendering of an unmanned offshore fish farm facility currently under development in Trondheim, Norway. © SINTEF

- Login to post comments